| |

Christmas Eve

A Report from Reuters,

December 24, 1941

Reports received from other sources said that even civilians and

British administrative officers were fighting with the arms they

could find and holding some isolated points. According to a last

communique issued in the morning of December 24th and received

at London by Reuters:

"The enemy made some progress during the early part of the

night, despite losses in the East point area. Heavy fighting is

in progress in the direction of Happy Valley, with our troops

disputing every foot of Japanese advance. Under strong enemy

pressure, we successfully evacuated our forces from Repulse Bay.

A further battle is in progress for possession for the Stanley

Peninsula."

By midnight of the 24th, the Royal Rifles were surrounded with

their backs to the sea. The following words about sum it up. Rfm.

Beebe from the Royal Rifles: "They came back again on the 24th

and we suffered heavy casualties on both days. There was no

eating or sleeping: it was fight, fight, fight! We knew the jig

was up but we were fighting mad and prepared to stand up to the

last man."

“It was the morning of December 25, 1941, in Hong Kong. The sun

shone bright and warm. Along the road bordered with blood-red

flowers strolled a Canadian soldier, steel helmet perched on the

back of his head and singing at the top of his voice. Fellow

soldiers taking cover in the basement of a house shouted at him,

"Take cover - get off the road!" The Canadian shouted back,

"It's a lovely day and it's Christmas morning." Then he picked

up his song and continued to stroll along the road, to disappear

forever.

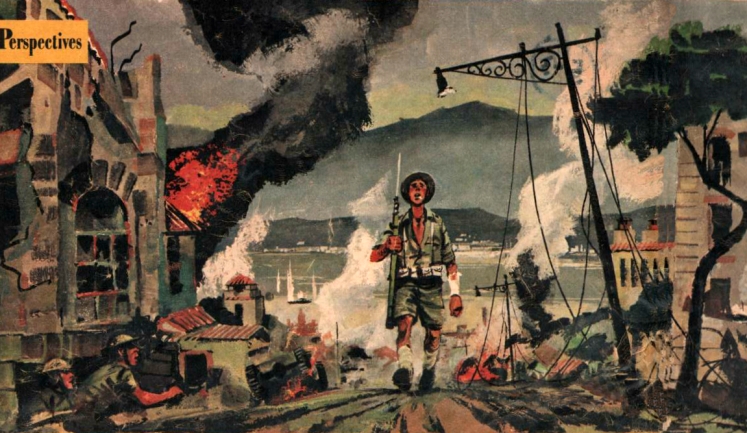

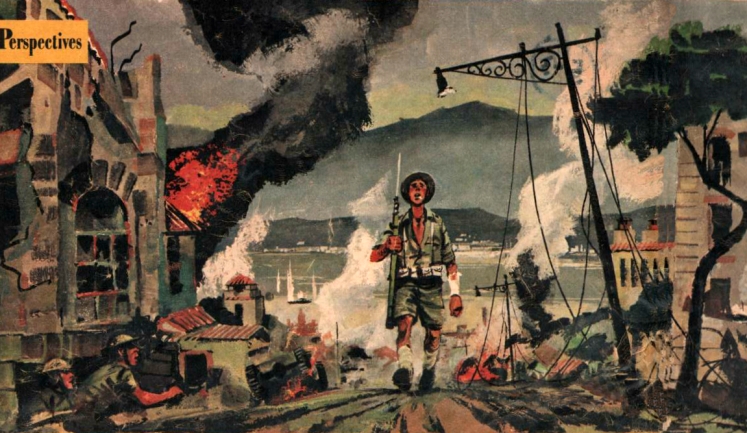

Above is an

artist's rendition of a shell-shocked and wounded Canadian soldier, singing as he

marches down a street in Hong Kong, oblivious of the madness and

mayhem around him. He was never seen again. Printed in the

Toronto Star Weekly, December 21, 1961. "Who he was, where he

came from and what eventually happened to him, the survivors of

the Winnipeg Grenadiers who had shouted out to him never did

learn. But the unreality of this occasion - the casual, singing

soldier strolling along, oblivious to the earth-shaking

explosions or the hills of Hong Kong which at that moment were a

mass of roaring flames - did not unduly amaze them. It was, so

they thought, merely an appropriate part of the greater

unreality which was the battle of Hong Kong itself. This does

not mean that there was anything unreal about the savage

fighting that had gone on for 18 days as 14,000 Canadian,

British and Indian troops attempted to hold off 60,000

experienced, superbly trained Japanese troops."

The mind can never really prepare for the horrors of war.

Nothing in a soldier's experience, nothing in training, can

prepare a soldier for the insanity which is war. The men of the

Royal Rifles of Canada were "Townshippers", from Quebec. The

Winnipeg Grenadiers were prairie boys, from Manitoba. They had

never fired a shot in anger, let alone with the intent to kill.

They certainly had never been shot at.

The sharp snap of a rifle

bullet overhead, the thump of an incoming mortar round, or the

earth shattering blast of an artillery round that falls nearby

are not the sounds for which one can prepare. The smell of

cordite, of burning fuel, burning rubber. The screams of the

wounded, the dying. A dead friend, alive a second ago, is

dismembered now. The coppery smell of hot blood that flows from

your own body is not something a soldier can be prepared for in

training.

To be under attack is to be in hell, an experience no normal

mind can really comprehend. To some it is unendurable. To endure

under attack is not just a matter of personal courage, it is to

know the instinct for survival intimately. To retreat into the

mind is not an act of cowardice. It, too, is an act of survival,

or a prelude to a death unchallenged, perhaps welcomed.

Their Finest Hour: "D" Company, the Royal

Rifles of Canada

The Royal Rifles of Canada had been pushed back down to the tip

of the Stanley Peninsula to Stanley Barracks. Some of the men

from "A" Company had just started to arrive to join "B", "C";

and "D" Companies for what was clearly the final battle. The new

front was a narrow line from the western to the eastern beaches,

near Stanley Village.

Like the men of The Light Brigade, there was water to the West

of them, water to the East of them, water at their backs.

Japanese artillery volleyed and thundered. No hope for victory,

no chance of rescue or relief, no place to go, just a burning

rage fuelled by frustration and the memories of butchered

comrades kept them going.

Under the powerful pressure of the constant bombardment the line

broke at its West end and sagged to the South, and East, and the

main body of "A" Company of the Royal Rifles was cut off at

Repulse Bay. The remaining defenders were squeezed into a thin

line along the East shore of the peninsula. And ... still they

did not give up.

The officers and men of "D" Company of the Royal Rifles of

Canada consider Christmas Day, 1941, to be their "finest hour".

They were to attack the Japanese in Stanley Village.

Major Parker Recounts:

"On the morning of December 25th .. I was called to Brigade

Headquarters at Stanley Barracks and met with Brigadier Wallis,

Colonel Home and Major Price who outlined the plans for an

attack on the Japanese troops concentrated in the Stanley

Village area. I was given a guide to conduct me and my Company

to the Stanley Prison, the start line of my attack. I was to

make a frontal advance to occupy the Ridge beyond the cemetery

and to retake the Indian Quarters on the right".

|